Toronto Star, Jul. 14, 2002

by Bill Taylor

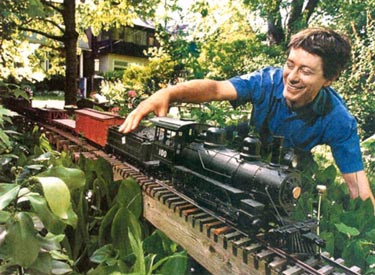

photo by Tony Bock / Toronto Star

Toronto Star, Jul. 14, 2002

by Bill Taylor

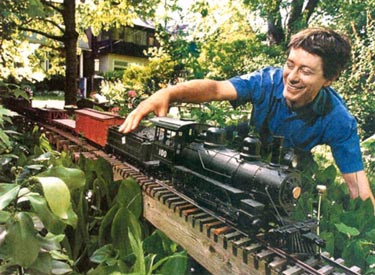

photo by Tony Bock / Toronto Star

What's the first thing you'd do when you moved into a new house?

Of course ... make a hole in the wall between the basement and the backyard big enough for a train to run through.

Doesn't everyone?

David Woodhead's expression is rueful as he contemplates the

tunnel that allows his miniature Newfoundland Railway trains to escape

from their

storage area out into the open air. There's been a fall of debris

— the work, he wonders, of a racoon saboteur or worse, far worse, a skunk?

— and he

may have to climb into a narrow crawl space to clear the line.

"No fun," he says.

Model trains are supposed to be fun. Woodhead and John Mishich

would tell you, yes, that's what they're having, even as they get into

some serious

stuff at the different ends of their hobby.

Woodhead wants his large-scale Annex garden railway to be as

realistic as possible. He didn't even buy his track from a store. He laid

his own, one

painstaking wooden tie at a time.

Mishich wants to get his small-scale Broadview Ave. apartment

railway into the Guinness Book Of Records. He's squeezed as much store-bought

track as he believes possible on to a 1.5-square-metre layout

in his bedroom. It totals almost 51 metres — more than Woodhead has in

his garden —

laid on half a dozen levels.

"I can run eight trains simultaneously," he says.

Woodhead tends to run his one at a time. His track is about 28

metres end to end. A train leaving the basement trundles past lily of the

valley, hostas,

forget-me-nots and ferns that look, in scale, like something

from The Lost World. Over a trestle bridge and then the rails disappear

behind the studio

where Woodhead's partner, ceramics artist Nancy Solway, works.

There's a Y-junction there where, with a little bit of switching, the train

can turn

around.

"I like it going from point A to point B rather than just around and around," he says.

"But I do have dreams of circumnavigating Nancy's studio. And

my neighbour told me, `Any time you want, you can expand into my backyard.'

That

would be great. She has a pond there!"

Woodhead, 50, is a bass guitarist, composer and producer. He's

been passionate about model trains, he says, since he got his first wind-up

set when

he was 4. His garden railway has been a decade in the making.

`They say they want records that are interesting,

safe, require skill and most importantly ... are

likely to attract challenges from other people. I

think I've met that completely'

— John Mishich, Guinness record aspirant

"I do it in little spurts," he says. "A week or two and I have something done. I guess this has been five or six spurts over 10 years."

Mishich, 47, works in security. He started his layout nine years

ago "to see where it took me. I'm always working on it. I hardly ever get

to actually

run the trains."

So far, the Guinness world-record people have refused to entertain

his suggestion of a new category: "The longest length of track in the smallest

enclosed area."

They say to get into the book, Mishich will have to beat the record for the longest model railway. And that has more than 15 kilometres of track.

"It takes up the whole of a three-storey building!" he says.

"I'm not knocking the guy, not at all, but I'm talking about something

entirely different.

Something anyone could do in a very confined space.

"They say they want records that are interesting, safe, require

skill and most importantly — this is what they say — are likely to attract

challenges

from other people. I think I've met that completely.

"But I'm not giving up on it. I think I have a legitimate argument

here. I mean ... a bunch of people go out and make snow angels and that's

a record?

Gimme a break!

"This ... this right here. This is a record. And I want to see people try to break it."

The layout has been put together with a surgeon's eye and a jeweller's

attention to detail. Pinprick red lights turn green as trains approach.

On the

lowest level, if you look closely, there's a "stream" running

the length of the track. Look a little closer and at one end there's a

mill, its water-wheel

turning. Look really closely and at the other end a couple of

guys are fishing.

All 1/160 the size of the real thing.

Woodhead's layout is somewhere between 1/22 and 1/24.

"People in this scale often use plastic track and ready-to-run

cars and locomotives," he says. "They're toy trains. I've always been a

builder. I've at

least repainted the cars and weathered them. I like to mess

around with stuff."

As he's talking, the bell breaks off the locomotive. "Oh, no!

Look at that.

`My neighbour told me, "Any time you want, you

can expand into my backyard." That would be

great. She has a pond there!'

— Model railroader David Woodhead

"Every inch of track is hand-laid," he continues. "I like the feel of working with metal and wood. I tried plastic ties but ... that's what they looked like.

"I use limestone screening as ballast. Every year it slowly washes away and has to be replaced, just like on a real railway.

"First thing in the spring, I have to level the track, check for frost heaves, just like real track maintenance.

"Yes, I can and do sometimes run in the winter. If it's the right

kind of powdery snow, I have a plough that goes ahead of the locomotive

to clear the

track. Otherwise I have to use a broom."

Garden railways aren't all that uncommon — Woodhead fishes out

a monthly magazine devoted to the subject — but, he says, "I'm the only

person I

know with an actual layout downtown. It's a suburban thing.

With spiffy backyards.

"A lot of them are into miniature plants and trees. Bonsai ...

yeah, there are guys who do that. We're not everything-in-its-place gardeners

here. I don't

mind if it all looks a little wild. It looks more natural. Real

railways aren't perfect; they're rough and ready."

He flicks fallen leaves from between the ties. A beetle clambers

laboriously over the rails. It's less of a worry than the big black ants

that keep

appearing.

"Oh, that's not good," says Woodhead. "They need watching."

His railway has six locomotives, "if I count unfinished projects," and a couple of dozen freight and passenger cars.

Mishich has lost count of his rolling stock, though it includes

everything from Wild West-era steam trains to up-to-the-minute Amtrak double-deck

Superliners.

Neither he nor Woodhead can put a dollar figure on their efforts.

"The real money is in the trains," says Mishich. "The time ...

how can you value the time you put in? Just to hand-make this trestle bridge

or this

viaduct, for instance ..."

Behind him are shelves filled with tiny tools and parts. There's

room for a few final centimetres of track to be added to the layout and

after that he

plans to put in a mountain-top golf course.

Two stations, Jennyville and Patricia, are named after his daughters. The Robert Michael engine house honours his late brother.

Woodhead has two sons, Daniel, 14, and Eric, 12. "But this has

always been Dad's thing. They take it so much for granted. When they were

growing

up, my kids probably thought every house had a railway in the

backyard."